| |

|

Mid-late

April

and

a

pair

of

turkey

vultures

check

out

a

shed

for

nesting

near

Wainwright.

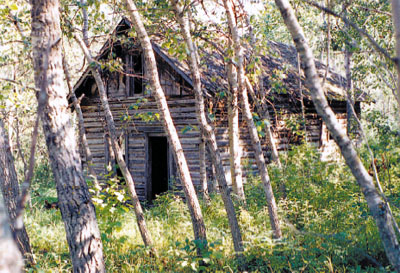

Surrounded

by

aspen

re-growth,

this

abandoned

farmhouse

near

Ernestina

Lake

had

vultures

nesting

upstairs.

An

old

barn

with

vultures

nesting

in

a

manger

accessible

by

the

small

lower

windows.

Thirty-five

and

33-dayold

vulture

chicks,

July

13

2004,

near

the

North

Saskatchewan

River

south

of

St.

Paul

.

Forty-two

and

44-

day-old

vultures.

Note

the

whitewash

on

the

walls. |

By

R.

Wayne

Nelson,

Floyd

Kunnas,

and

Dave

Moore.

Charisma?

Despite

its

almost

two-metre

wingspan,

its

amazing

ecosystem

function

and

services,

and

its

spectacular

soaring

ability,

it

is

difficult

for

some

people

to

refer

to

turkey

vultures

as

“charismatic

megafauna”,

but

they

definitely

are.

Their

wingspan

is

three-quarters

that

of

golden

and

bald

eagles.

Their

naked

heads

are

like

those

of

turkeys,

which

prompted

their

name,

but

the

function

of

that

nakedness

is

entirely

different.

As

large

avian

scavengers,

vultures

clean

up

large

and

small

“deads”

by

ripping

through

skin

or

holes

in

dead

animals

and

eating

the

material

inside.

Inside

a

dead

cow

or

road-killed

deer

can

be

very

messy

and

a

naked

head

is

a

valuable

adaptation

for

avoiding

a

“bad

feather

day”.

Vultures

sometimes

feed

on

road-killed

skunks,

which

may

seem

gross

to

us,

but

is

obvious

to

vultures

because

they

have

an

amazing

sense

of

smell.

In

contrast

to

most

other

land-birds,

turkey

vultures

can

smell

well

and

can

locate

even

lightly

buried

decaying

meat

from

long

distances

downwind.

We

are

stretching,

perhaps,

but

even

that

adds

some

charisma.

Living

the

slow

life

Vultures

do

not

live

in

the

fast

lane.

In

the

morning

they

are

content

to

remain

at

their

community

roost,

soak

up

the

early

morning

sun,

wait

for

the

cool

air

to

warm

up,

and

then

slowly

flap

to

a

thermal

to

catch

its

lift

or

use

the

slightest

breeze

or

uplift

from

a

river

valley

wall

to

rise

and

soar

and

glide

across

large

parts

of

the

landscape,

smelling

for

dead

food

and

watching

afar

for

signs

that

other

birds

or

mammals

have

found

some.

Even

their

nesting

is

a

relaxed

affair.

Vultures

arrive

back

in

the

spring

at

the

latitude

of

Hairy

Hill

and

Elk

Point

just

after

the

middle

of

April.

The

vultures

lay

their

eggs

(usually

two)

in

early

to

mid

May,

quite

late

in

the

spring

for

a

large

bird.

After

38-40

days

of

incubation

by

both

parents

their

eggs

hatch

in

mid-late

June.

After

about

two

months

in

the

nest

the

nestlings

have

grown

to

adult

size

and

make

their

first

flights,

usually

in

mid-late

August

or

early

September.

At

one

nest

at

which

the

nestlings

first

flew

about

September

9,

they

were

still

present

near

their

nest

in

the

early

morning

of

September

29,

and

the

landowners

last

saw

vultures

in

the

vicinity

on

the

following

day.

Vultures

have

a

late

and

long

nesting

season

before

migrating

to

southern

climates

for

the

winter.

Big,

but

elusive

In

addition

to

having

a

very

interesting

and

slow

life-style

and

being

a

very

large

bird,

vultures

can

be

very

secretive.

In

eastcentral

Alberta

in

the

1980s

and

1990s,

Fish

and

Wildlife

offices

received

occasional

reports

of

sightings

of

vultures

and

a

few

discoveries

of

vulture

nests.

Wildlife

biologists

tried

to

visit

these

nests

annually.

In

the

late

1990s,

several

of

our

historically

occupied

sites

were

destroyed

and

several

others

were

regularly

unoccupied,

and

we

began

to

advertise

our

interest

in

locating

additional

vulture

nests

in

newspaper

articles,

at

post-hunting

season

meetings

and

at

other

opportunities.

|

In

2003,

perhaps

due

to

our

interest

in

vultures

reaching

some

critical

mass,

public

reports

suddenly

raised

our

list

of

active

vulture

nests

to

nine,

and

in

2004

we

had

14

pairs.

Despite

our

advertising,

we

also

received

several

phone

calls

from

people

who

had

no

idea

that

we

were

interested

in

vultures,

that

went

something

like,

“Hello,

umm,

uh,

this

may

sound

like

a

stupid

question,

but

do

we

have

vultures

in

Alberta?”

To

which

we

would

answer,

“Yes.

And

did

you

by

chance

see

one

perched

on

the

roof

or

in

the

window

of

an

old

abandoned

farmhouse

or

barn?”

“Yes!

How

did

you

know?”

We

ask

where

they

saw

it

and

tell

them

we

will

be

back

in

touch

in

July

or

early

August

to

check

to

see

if

the

vultures

have

youngsters

in

the

buildings;

and

we

ask

them

to

not

disturb

the

vultures

at

the

buildings

because,

if

visited

before

egg

laying,

they

almost

certainly

will

abandon

the

site.

We

also

tell

the

enquirer

that

although

turkey

vultures

live

in

South

America,

Central

America,

Mexico,

and

the

southern

U.S.,

they

also

nest

northward

through

the

U.S.

and

into

southern

Canada,

and

in

the

Edmonton,

St.

Paul,

Cold

lake

area,

we

are

at

the

northern

edge

of

this

vulture's

breeding

range.

Nest

sites

Elsewhere

in

North

America,

turkey

vultures

traditionally

nest

on

the

ground

under

dense

bushes

or

under

logs,

in

large

hollow

logs

or

in

cavities

beneath

wind-tossed

trees,

especially

on

islands

that

provide

protection

from

terrestrial

predators.

They

also

regularly

nest

in

rock

jumbles

and

in

potholes

or

caves

in

cliffs.

Rarely

do

they

use

other

birds’

large

stick

nests

in

trees.

Occasionally

they

use

abandoned

buildings,

however,

in

east-central

Alberta

all

of

the

sites

that

we

have

learned

about

in

recent

years

have

been

in

abandoned

buildings.

In

the

Red

Deer/Big

Valley

area

we

have

been

told

of

one

nest

in

a

building,

but

the

few

other

known

nests

in

that

area

and

near

Medicine

Hat

appear

to

be

in

the

usual

cliff

settings.

Our

vulture

buildings

to

date

have

shared

several

characteristics.

None

of

these

buildings

can

be

seen

from

an

active

human

residence

or

farmyard.

From

their

building

the

vultures

may

be

able

to

see

a

busy

highway

only

100

metres

away,

but

very

rarely

is

there

pedestrian

activity

there.

Their

abandoned

farm

buildings

usually

are

in

or

adjacent

to

pastureland

rather

than

cropland.

Almost

all

of

the

vulture

buildings

are

close

to

or

snug

against

or

actually

within

a

grove

of

trees.

The

buildings

themselves

can

be

quite

different.

One

was

an

old

dance

hall,

but

it

has

recently

decayed

so

badly

that

the

vultures

do

not

use

it.

Several

are

still-solid

old

farmhouses

with

the

nests

in

upstairs

rooms

with

access

gained

through

missing

windows,

or

with

nests

in

attics

with

access

gained

through

missing

outside

doors

or

windows

or

through

missing

shingles

on

the

roof.

Some

are

accessible

by

walking

up

stairs,

others

require

ladders.

All

require

caution!

Some

are

in

old

barns.

One

pair

nests

in

the

manger

of

the

main

level

of

a

huge

80-year-old,

hip-roofed

barn,

gaining

access

through

small

windows

about

two

metres

above

the

floor.

This

pair

failed

in

2004

because

the

barn

roof

leaked

and

heavy

rains

soaked

the

eggs

and

nesting

substrate

straw

in

the

manger.

Because

vultures

do

not

actually

build

nests,

they

require

some

material

that

will

prevent

their

eggs

from

rolling

away.

The

substrate

may

be

shavings

used

as

insulation

between

the

joists

in

an

attic

or

it

may

be

wind-blown

dirt

in

a

corner,

rags

or

other

attic

debris.

Even

a

layer

of

dried

pigeon

manure

on

the

floor

will

suffice.

Usually

the

nest

is

in

a

corner

or

at

least

against

a

wall

or

sloping

roof.

A

close

look

at

our

study

area

indicates

that

there

are

still

many

old

farm

buildings

scattered

about

the

landscape,

some

of

which

have

vulture

potential.

We

worry

a

bit

about

their

limited |

Approximately

55

and

51-

day-old

vultures,

31

August

2003,

near

Hairy

Hill. |

life

expectancy

and

where

the

vultures

will

nest

in

another

50

years

when

almost

all

of

these

old

buildings

have

finally

collapsed.

In

the

meantime,

we

ensure

that

the

landowners

are

aware

of

these

unique

and

interesting

creatures

inhabiting

their

buildings.

We

encourage

them

to

let

the

buildings

stand

for

as

long

as

possible.

A

few

of

the

landowners

are

planning

wintertime

repairs,

so

their

“vulturarium”

will

be

dry

and

durable

for

at

least

a

few

more

decades.

These

abandoned

farmsteads

are

often

used

by

a

variety

of

other

wildlife

species,

but

none

so

secretive

as

the

vultures.

|

Many

landowners

have

no

idea

that

these

huge

birds

are

nesting

in

their

abandoned

buildings.

Not

only

are

the

chosen

buildings

tucked

away

in

quiet

areas,

the

vultures

are

ultra-cautious

when

returning

home.

They

appear

to

scout

the

area

carefully

for

danger

from

afar

and

glide

a

number

of

lower

and

lower

sweeps

in

the

immediate

vicinity

before

finally

committing

themselves

to

land

at

their

nest

or

at

a

potential

food

item.

They

may

be

able

to

smell

a

person

who

remains

in

the

vicinity

of

their

nest,

hidden

in

a

blind

that

would

trick

almost

any

other

bird.

But

the

parent

vultures

do

return

to

care

for

their

youngsters

after

humans

have

departed

the

nest

site,

despite

any

whiff

of

human

odour

that

is

left

behind.

Usually

the

adults

are

not

present

when

we

visit;

perhaps

they

are

far

off

and

foraging.

Occasionally

one

or

both

have

appeared,

perched

in

a

distant

tree,

as

we

have

exited

their

nest

building.

Productivity

and

site

fidelity

Of

the

nine

nests

we

visited

in

2003,

eight

held

two

nestlings

and

one

held

one,

for

a

total

of

seventeen.

In

2004

our

informants

brought

the

number

up

to

14

pairs,

of

which

seven

broods

had

two

nestlings,

three

had

one,

again

for

a

total

of

seventeen.

Of

the

other

four

pairs,

we

know

that

two

failed

during

incubation

(broken

or

abandoned

eggs)

and

from

their

behaviour

we

think

that

the

final

two

pairs

had

nestlings

close

by,

but

we

and

our

helpers

could

not

find

the

nests.

From

2003

to

2004,

two

pairs

moved

their

nests

nearby

and

the

other

seven

used

the

same

site

in

both

years.

In

2004

another

nest

was

used

after

a

lapse

of

at

least

three

years.

Of

the

sites

new

to

us

in

2004,

two

were

known

by

local

families

to

have

been

used

for

several

years

previously

and

one

was

definitely

a

new

site

with

the

amount

of

“whitewash”

on

the

walls

and

floor

representing

only

the

2004

brood.

Nesting

Range

In

Alberta,

vultures

are

documented

as

nesting

in

the

Grassland

Natural

Region

in

the

Cypress

Hills

near

Medicine

Hat

and

in

the

Big

Valley/Red

Deer

area.

In

the

Parkland

Natural

Region

they

nest

near

Chauvin

and

Wainwright,

near

the

North

Saskatchewan

River

south

of

St.

Paul

and

near

Duvernay,

south

of

Two

Hills

near

Hairy

Hill,

and

south

of

Waskateneau.

In

the

early

and

mid

1900s

vultures

nested

in

the

isolated

patch

of

dry

mixed-wood

to

the

southeast

and

east

of

Edmonton

at

Miquelon,

Ministik,

and

Astotin

Lakes.

In

the

main

body

of

the

dry

mixed-wood

portion

of

the

Boreal

Forest

Natural

Region,

a

ground-nest

of

vultures

was

found

in

Cold

Lake

Provincial

Park

in

the

1970s

and

more

recent

nests

in

buildings

have

been

found

near

Angling

Lake,

Ernestina

Lake,

the

Beaver

River

north

of

Bonnyville,

Moose

Lake,

Elk

Point,

St.

Paul,

and

in

the

1950s-1970s

at

Mann

Lakes.

The

Cold

Lake

and

Beaver

River

sites

are

the

farthest

north

nests

known.

Numerous

sightings

near

Lac

La

Biche

suggest

that

eventually

vultures

will

be

found

nesting

there

too,

pushing

the

breeding

range

farther

north.

To

date,

in

our

east-central

Alberta

study

area,

all

of

the

nests

have

been

within

a

rough

triangle

from

Provost

to

Edmonton

to

Cold

Lake,

with

the

bulk

of

the

nests

in

the

northern

half.

From

our

own

observations

and

those

of

others,

we

strongly

suspect

that

our

east-central

Alberta

population

of

vultures

is

increasing,

similar

to

but

much

more

discretely

than

the

recent

increases

in

the

common

raven,

osprey,

bald

eagle,

and

cougar

in

this

area,

perhaps

resulting

from

less

random

shooting

of

“varmints”,

less

poisoning

of

large

and

small

wildlife,

and

a

burgeoning

white-tailed

deer

population

with

its

abundant

road-kills.

Searching

for

vultures

In

Saskatchewan,

beginning

in

2003,

researchers

have

attached

wing

tags

to

nestling

vultures

when

they

were

nearly

full-grown.

Those

wing

tags

are

on

the

right

wing,

green

with

large

white

numbers

and

letters,

about

the

size

of

a

large

cattle

ear

tag,

and

are

readable

with

binocs

or

telescope

at

long

distances,

whether

the

vulture

has

its

wing

open

or

closed.

Please

report

sightings

of

wing-tagged

vultures

to

the

Bird

Banding

Office

at

1-800-327-BAND,

and

to

Stuart

Houston

at

(306)

244-0742

or

houstons@duke.usask.ca

We

may

be

able

to

undertake

a

similar

wing

tagging

program

in

Alberta

to

try

to

learn

about

movements,

fidelity

to

natal

areas,

age

at

first

breeding

and

many

other

aspects

of

the

lives

of

the

known

individuals.

If

we

can

locate

15-20

active

vulture

nests,

and

if

their

annual

return

to

those

nests

is

relatively

high,

we

may

be

able

to

efficiently

monitor

(say,

every

five

years)

the

productivity

and

health

of

this

population

and

the

health

of

that

very

interesting

part

of

the

environment

that

they

sample.

For

the

part

of

the

province

north

of

Highway

13

(Provost

-

Camrose

-

Pigeon

Lake

-

Alder

Flats),

we

request

reports

of

all

vulture

sightings,

and

especially

any

sightings

of

vultures

on

or

in

buildings.

Vultures

have

two

serious

chinks

in

their

secrecy

at

their

nest

sites,

which

allow

vigilant

observers

to

find

them.

In

mid-April

to

mid-

May,

having

just

arrived

back

from

Texas,

Mexico,

or

points

south,

adult

vultures

engage

in

several

weeks

of

courtship

with

followflights

and

other

aerial

displays.

But,

importantly,

they

spend

some

time

perched

on

the

roofs

or

in

the

windows

of

their

nest

building

or

in

large

trees

close

by.

In

mid-August

to

late-September,

young

vultures,

recently

out

of

the

nest,

perch

conspicuously

in

the

windows,

on

the

roof

and

near

their

nest

building,

between

practice

flights

in

the

area

and

while

awaiting

their

parents’

return

with

tasty

treats.

Charismatic

megafauna,

indeed!

Wayne

Nelson

is

the

Area

Wildlife

Biologist

for

the

Fish

and

Wildlife

Division

(FWD)

in

St.

Paul.

Floyd

Kunnas

is

the

Senior

Wildlife

Technician

for

the

Northeast

Region

FWD

in

St.

Paul.

Dave

Moore

is

the

Area

Wildlife

Biologist

for

FWD

in

Vermilion.

Contacts

for

vulture

sightings:

rwayne.nelson@gov.ab.ca

floyd.kunnas@gov.ab.ca

dave.moore@gov.ab.ca

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|